Less Is More When Grading Papers

For many instructors, grading papers can be a tedious task.

For many instructors, grading papers can be a tedious task.

Do you ever tire of underlining comma splices or circling misplaced modifiers? Do you wonder how you will ever teach your students about subject-verb agreement, let alone what makes an effective topic sentence? Well, we at the OWL have some good news for you:

Stop worrying.

When it comes to grading papers and giving helpful feedback, we have found that, in the end, less is more.

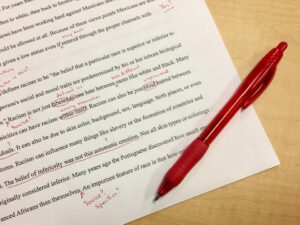

Decades of research show that not only do old-fashioned grammar lessons not help students learn how to write, but that they may even create a distaste for writing among some students. As hard as it may be to give up trying to show your students the errors in their writing, we suggest doing just that. Throw away your red pens, virtual or real, and take on a whole new approach, one we will outline here. Not only will you save yourself lots of time, but your students will also be better positioned to tackle rewrites and improve their work.

Beth Hewett, PhD, a writing and bereavement coach, has been writing about the pedagogy of writing for two decades. Her articles and books are based on years of experience and research in the field of teaching writing, especially online. In her book Reading to Learn and Writing to Teach (2015), Hewett outlines what she has found to be the most useful guidelines for instructors who are hoping to find more success, engagement, and growth in their students’ writing journeys. In this post, we have distilled her main points for you so that you can apply her suggestions to your own courses and feedback process right away.

We have found from experience that the steps outlined below, structured on Hewett’s advice for teaching writing online, will not only save time by streamlining the grading process, but they also provide students with meaningful feedback with which they will be likelier to engage.

1. Stop correcting every grammar, punctuation, and usage error. Just read the paper through—first once quickly—to see if it meets length requirements, uses sources and citations, follows your style guide, and meets any other core rubric elements.

2. Next, read the paper more carefully, looking for higher order requirements such as a strong thesis, good overall organization, well-placed citations, and fluency of argument.

3. Choose 1-2 areas on which to focus your feedback. Avoid discussing grammar or usage problems unless one is so prevalent it demands your attention.

4. Structure your feedback using Hewett’s “What, Why, How, Do” format, in which you explain what needs attention, why it needs attention, how to embark on making changes, and an action item the student can address in their revision or next assignment.

At first, fulfilling this process might feel like more work. But, if you dedicate yourself to this change in how you provide your instructional feedback, you will quickly find that you are spending less time in total on each student paper, providing more concrete feedback that will result in improved writing for your students, and very likely enjoying the process much more.

For more resources on teaching writing and giving good feedback, you can consult Beth Hewett’s renowned work, Reading to Learn and Writing to Teach.